I here share with you a paper that I wrote in preparation for my role as keynote-speaker for the Giving Women Conference in Geneva in October 11th, 2018. This paper has not been shared publically before. And although it was written six years ago, its messages are still as valid and significant today. Hope you enjoy it. See also the live recordings from the event via links at the bottom of this article.

Circular fashion – empowering women to act as “local change agents”

How can women in developing countries benefit from the circular fashion era? Women within the fashion industry have long been regarded as victims, suffering from poor working conditions, low wages, inequalities, environmental destruction etc. Yet, as the concepts of circular economy and circular fashion are spreading across the world, women may now come to play an increasingly significant role within our global society – as change agents that can drive development from local level and up.

Traditionally, women have typically been responsible for managing most of the household chores, including making and mending clothes and other home textiles for the family, even redesigning and reusing the textiles for new purposes. In today’s modern society, however, most women have lost much of these skills over the past half century, as fashion has become increasingly affordable and accessible for most people. Instead of reusing garments and textiles within the household, we now go shopping for the newly produced, perhaps out of convenience, time pressure, or a desire for something new.

However, as the agenda around sustainability and circular economy is growing stronger, we now understand the importance of making use of existing textiles and other manufactured products on a far greater scale. Unfortunately, much of the tailoring, mending and redesign skills that existed in practically every households only 70 years ago, are now largely lost in the West. Of course, tailors and seamstresses still exist in most cities in Europe and the US. Yet, even the idea of prolonging the life time of our textiles through mending, redesigning etc. is rarely not even given a slight thought for Western “modern” family.

Meanwhile, the majority of women in developing countries still possess and practice these important skills and knowledge on a daily basis (most likely). Imagine if these skilled women could be seen as “sources of vital competence” for the global circular economy. What if they could be empowered as change agents to enable and facilitate local solutions for the textile economy, in parallel with large-scale global and regional solutions?

Circular textile solutions are needed, locally and regionally, for social and environmental reasons. Working at all levels of society is necessary if we wish to create a truly sustainable and circular fashion and textile industry. Women here have a vital role to play. Design ANYWHERE, but source, produce, repair, redesign, reuse and recycle LOCALLY as a priority option”, could be our mantra.

Compassionate fashion – heart-led, not only mindful

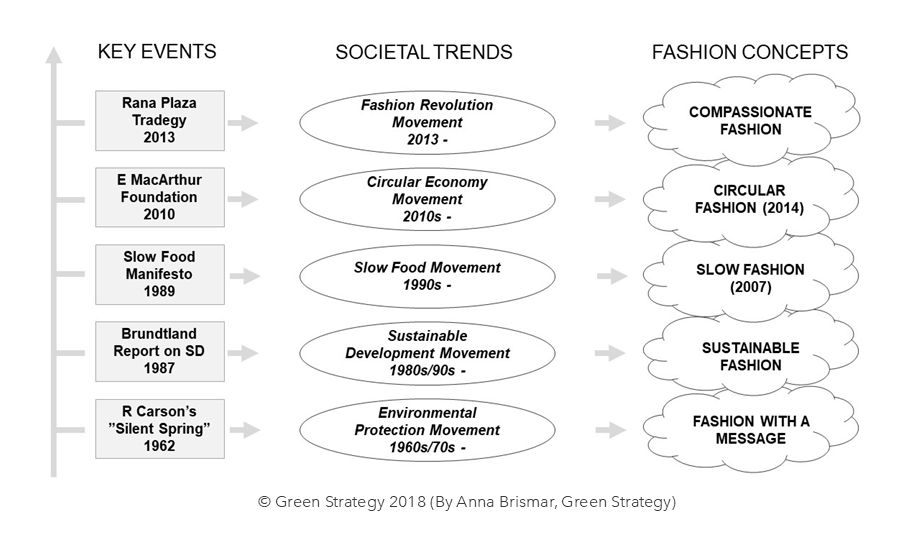

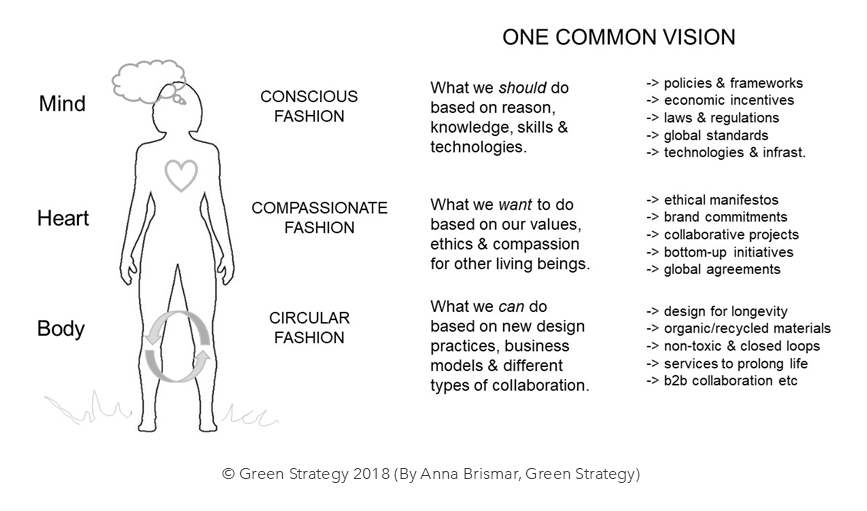

What is compassionate fashion? How could this concept change the way fashion companies are acting across their supply chains and towards stakeholders? Another concept that has entered the scene, and which are likely to grow stronger over the coming decade, is “compassionate fashion”. Essentially, this term can be boiled down to three other C-words: “Care, Commitment and Consistency.”

Although sustainability has never been more important and widely addressed, the term sustainable fashion has in part become diluted as many companies are articulating a strategic ambition to be sustainable, yet not truly acting in alignment with this ambition on a practical level. For example, organic cotton may make up a larger share of the fabrics in their children’s wear; yet the same t-shirts and underwear are covered with plastic prints and made in less-developed countries, such as Bangladesh, where low wages and poor working conditions are prevalent.

Compassionate fashion, by definition, is based on a clear set of values with a commitment to act upon these values with consistency, and without compromise or exception. Thus, while “conscious fashion” is primarily based on an awareness of sustainability in more theoretical terms, compassionate fashion is based on heartfelt values that are formed at the center of the company and embraced and acted upon with integrity.

In other words, it is not simply enough to have a beautiful sustainability report or website with well-articulated visions such as “to run a long-term sustainable business within our planetary boundaries”, or “to create the best offering for our customers, in the most sustainable way.” It must be evident for everyone– customers, employees, media and all other stakeholders – that the company makes no compromises with its core values at no time, nor place. The core values should guide and dictate ALL decisions within the company. If not, the company may eventually loose trust, respect and credibility.

A transition from mere consciousness to genuine compassion means that companies will begin to lead ‘from their heart’ as opposed to simply ‘from their minds.’ The ambition of such companies will not simply be to minimize or compensate for any adverse impacts, but rather to prevent any negative impacts at all costs, and to create positive outcomes and long-lasting benefits to others. This new approach originates in the precautionary principle and the idea of doing good, rather than just focusing on doing less bad.

In the coming decade, we are likely to see more fashion-consumers demanding from the brands to demonstrate a clear set of values and be committed to them at all times. Hopefully, the fashion industry will – in response – gradually open up to this fundamental shift from simply “articulating consciousness” to also feeling and acting upon true compassion towards how people, animals and ecosystems are affected across the supply chain. Already, we can see that the words “alignment and integrity” are entering the sustainable fashion arena.

Hopefully, as more women retain leading positions in society, they will be able to spread the concept of compassionate fashion, where the company values are not simply beautiful statements in documents and on websites, but also values that are acted upon with consistency and integrity, thus creating trust and credibility for all parties, and doing good for the World. (Anna Brismar, 2018)

On-demand fashion – avoiding over-production and -consumption

What does on-demand fashion mean, and how would you say it is the missing piece in the puzzle? Over the coming decade, we are likely to see a third trend within the fashion industry. Consumers are likely to grow increasingly tired of the mass-produced, fast-to-market and similar-looking fashion styles that dominate the market today. Instead, we are likely to see a rise in the demand for more personalized items of higher quality, which are produced ‘on-demand’ (e.g. tailor-made, custom-made and bespoke items). ’Fashion on-demand’ has been identified as “the missing piece in the puzzle” already in 2013 but is now finally emerging on a broader scale.

‘Fashion on-demand’ implies that the customer can choose his/her preferred style, fabric, size and possible details from a range of pre-designed options, thus “co-creating” an item of choice before production. The store is essentially a showroom and the order would normally not take more than three weeks. With ‘fashion on-demand’, consumers are likely to develop greater emotional attachment to their garments and hold on to them for longer. On-demand production will also reduce the need for storage and the risk of over-production, thus minimizing textile waste, landfilling and incineration, as well as the use of virgin natural resources and the risk for adverse environmental impacts across the supply chain.

One of the problems with today’s ready-made society is that it creates an impression that consumers cannot be held responsible for an unsustainable act of buying and accumulating too much products, as they have not been involved in the creation at any point across the value chain. What is not evident to most people however is that production is actually based on previous sales numbers and past consumer behavior. (Anna Brismar, 2018)

Today’s ready-made society is essentially the result of “planned obsolescence”, a widely spread strategy has dominated our modern industry since the 1950s. This strategy implies that products are designed and manufactured at the onset with the aim of becoming obsolete within only a short time span, typically due to broken parts (which were intentionally made to break easily), an impoverished functionality (intentionally made to be weak) or an outdated style (intentionally made to be replaced by a new style). In this way, the industry is able to create an endless demand for new products. With this short-term profit-focused strategy, a global market of ready-made products is created and maintained. Companies today rely heavily on this inter-dependency between consumers and their market shares.

Yet, the truth is, most people in developed countries rarely need mass-produced ready-made products, may it be clothes, home textiles or IT-devices. The need to fill our homes with additional stuff is no longer real. This may have been true in the 40’s or 50’s, when we still had some concrete need for additional basic garments and household items. Today, however, people have overfilled homes and instead long for the “exclusive” and items that hold personal meaning and add special value to their life.

The time has come for our global manufacturing industry to transition from this “ready-made production approach” to an “on-demand production strategy”. We need to build industries that are meant to serve people’s actual needs. This in turn will enable us to create a society in which our true needs are met, in an ethical and overall sustainable way.

—-

This article was written by Anna Brismar (October 2018) for the Giving Women Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, October 11-12, 2018. (Here published for public access.) For referencing, please use the publication date (2025.02.05).

To see live recordings from the event, please click on these links from Facebook:

- https://www.facebook.com/giving.women/videos/860167657513080?locale=sv_SE

- https://www.facebook.com/giving.women/videos/309666783148367?locale=sv_SE

See also this article for a summary of the actual presentation at the Giving Women Conference:

Some photos from the event: